The first Icelandic LazyTown play that I saw was Áfram Latibær. It was at a time when I was still a budding LazyTown fan, and still adamantly digging my way into the concept to see what was at the center. When I came across the play, I thought I had taken a wrong turn somewhere. I was in quite literal disbelief. Even though I was told that this was supposed to be LazyTown, surely someone somewhere got something terribly wrong. Seeing these weird looking characters running around these weird looking sets, singing these weird sounding songs just did not register with me as being correct, despite the fact that that description sounds exactly like present-day LazyTown. I double checked and triple checked, and everything kept telling me that yes, this was right; what I was watching was LazyTown. That’s when the word “Latibær” (Icelandic for LazyTown) became part of my vocabulary, and I began to consume everything that I could find with that in the title, beginning with the continuation of Áfram Latibær, the first of three pre-TV series LazyTown plays.

A still from Áfram Latibær

It was at about this point that I thought something was wrong

I soon found myself neck deep in the bizarre, absurd, and whimsical world of LazyTown circa late 90’s and early 2000’s. The only thing keeping me from going all the way under, was the obvious question of, “But what are they saying?” That question stayed mostly unanswered for the next several years. Even though an English translation of the plays was in high demand by LazyTown fans, translating the plays was no small task. The obvious challenge was the sheer amount of work that would have to go into it, as the shortest is still nearly an hour long, but a more hidden challenge is the fact that there are relatively few Icelandic speakers in the world, so finding one to help with the project was more difficult than if it had been a Spanish to English translation, for example. Regardless of the challenges that the project faced, every so often, someone would try to take it up. Usually, it would be an Icelander who would enthusiastically come out and say, “I’m going to be the one who does it! I’m going to be the one who translates the plays!” Then they would translate, say, the first five minutes of one of the plays, and then never be heard from again. You can still find relics of work like this in videos on YouTube, which have commenters begging in vain for them to be continued. Sometimes a fan would come by and try to make something happen using Google Translate and song lyrics, and while it was something, it obviously didn’t paint the full picture, and there was still an awful lot lost in translation. Even I had personally looked into doing it, and researched the possibility of using a professional translating service. It’s a pretty good idea until you see the price tag. It would be about $1,000 per play for an Icelandic to English translation, which is more than most would be willing to fork out. I admit that after years of the same old disappointments from fizzled attempts, I had given up hope that this was ever going to happen, unless I somehow hit it big and could throw around 3,000 dollars like it was nothing. I guess most of the other dedicated LazyTown fans came to a similar conclusion, because it was not really seriously brought up for years on end.

One day in early 2016, an up-and-coming LazyTown fan who goes by the handle of “Fox” decided, like all up-and-coming LazyTown fans do, that the plays needed to be translated. However, he had a different approach than most of the people in the past, who had simply banked on the generosity of an Icelander to get the job done. Not that Icelanders are not generous, but Fox knew that you had to get the green flowing before anything would ever happen. By the time he said anything to the rest of us, he had already gone ahead and purchased a few minutes of translation of the second play, Glanni Glæpur í Latabæ. He purchased the service from an Icelandic native named Kristófer on a website called fiverr.com, where people sell small services for a fee of five dollars. Kris was selling Icelandic to English translations, in chunks of a few hundred words at a time. I had not heard of the site before, and given my past experiences, I was still skeptical that this would turn into anything big. But in short time, the guy delivered, and Fox wanted to continue to pursue this option to eventually get the entire play translated. I figured why the hell not, and despite my skepticism, I more or less took charge of the project to see how far it could be taken.

I agreed with Fox that Glanni Glæpur í Latabæ was the correct place to start, so I kept down that path. That may not seem logical because it is the second play and not the first, however, the reason why I thought it should be done first was rooted in the fact that there have been so many flakes in the past. I hedged my bets on the side of pessimism to account for the possibility that Kris would flake at some point, and decided that if I had to choose just one play to be translated, even if it was only a piece of it, it would be Glanni Glæpur í Latabæ. I think most LazyTown fans would feel the same way, and I’m pretty sure that that’s similar logic that Fox had when he got the wheels turning on the project.

I spoke with Kris, thanked him for what he did so far, and asked him if he wanted to continue working on translating the play until completion. He said that he would, so we proceeded to negotiate the terms. We had to move away from Fiverr at this time, because their service structure is pretty strict; you pay exactly five dollars for exactly whatever service is advertised, which wouldn’t work well with what we would be doing. We agreed that we would just use email as the main communication channel, use Paypal for payment, and we eventually landed on a price of $130 for a transcription and translation of the entire hour-and-a-half-ish long play. We both had to take a little leap of faith here since this would not be done through a managed structure like Fiverr. Not everybody is willing to take a risk like that, so I’m grateful that Kris somehow found enough trust in a stranger to take me up on the terms. I was also grateful to see a price that would be much more manageable for the average Joe like myself. So just like that, we had begun.

Even though Kris and I had worked everything out, I was still jaded from my past experiences and still wasn’t really convinced deep down inside that this was going to work. Well, spoiler alert, it absolutely did. Kris totally delivered on his promises and then some, and we were able to not only get Glanni Glæpur í Latabæ translated, but also the other two plays, Áfram Latibær and Jól í Latabæ as well. There will be more details on how each of those projects went individually in later blog posts, but here, I’d like to give you an idea of how the general translation process worked. Admittedly, the process of translating is actually very dull, but if you’re reading this, hopefully you’re the kind of person who would want to learn about it anyway. It goes without saying that as Kris and I progressed through the projects, our methods tightened and changed a little bit from what I’m going to explain, but you’ll get the idea of how it went down.

We would start out with Kris transcribing an entire play in Icelandic and sending it to me, at which point I would pay him whatever agreed upon amount for the transcription; usually a little less than half of the total price. The only meaningful thing that I could do with the transcription at this point was begin laying out the timing of the lines for the subtitles, which I mostly avoided doing. Although it was slightly more efficient for me to do so, it could complicate things later if some of the lines actually read a lot longer in English than Icelandic, which would cause me to need to split up the lines and then re-time them and then shift everything else accordingly and so on. So I just didn’t even bother. I told you this was dull. Are you still reading?

Immediately after the transcription was done, Kris would begin the translation. Instead of sending it as a whole like the transcription, he would send it to me in chunks as he completed it. This would allow me to get to work as soon as possible, and the method greatly cut down on the overall time that the projects took. It also allowed us to build trust with one another, as I would pay him per chunk. Once I had some parts flowing in, I would begin by interpreting the lines into “real” English, meaning English that was actually intelligible and that sounds like it was coming from a native speaker. I would use the Icelandic transcription a lot during this process to ensure that I was keeping the original meaning as true as possible by referencing the sentence structure, the surrounding context, isolating words, and using my knowledge of English, Icelandic (albeit small), and language in general to guide me. It goes without saying that Kris did interpretation while he translated, but given that he is not a native English speaker, there was still a lot for me to do as far as rephrasing, fixing grammar, or even flat out changing things whenever appropriate. Similarly, some localization had to be done from time to time. The dialogue would occasionally have references to Icelandic cities, puns, traditions, and so on, that absolutely made no sense in English. Lines like this had to be modified with special attention to ensure that it made sense in English while still keeping the core of the meaning. Kris would usually make a little aside in the translation if there was anything strange like this that needed some extra explanation, which was very helpful and very appreciated. If anything still didn’t exactly make sense to me after Kris’s and my own efforts, I would take note of it to later send in for review. I would say that only 1-2% of lines had to get that treatment.

I would also throw in a little bit of sneaky fan service here and there, by retooling lines to retrofit them with current-era lines or gags. For example, changing one of Stingy’s lines from, “I own that bus stop,” to, “That bus stop is mine!” Or, admittedly less elegantly, changing a line that went, “Stephanie the Stiff I surely was,” to, “I was one stiff Stephie,” which is not only a nod to the lyrics of the same song remastered for the television series, but it’s also a brilliant way to slip past the complications of the characters’ surnames… more on that in a later post.

People who have only seen the final product might be surprised at how much changes from the initial translation to what ends up on the screen. When I started out, I was a little more of a purist, and was slightly uncomfortable even rephrasing a line. As time went on, I came to realize that what the characters say is less important than what the characters mean, and began to wield artistic license more willingly. Below is an example of how the dialogue evolves. Keep in mind that while it is a really good example in my opinion, it is also on the more extreme end. Here, Sportacus tells Pixel a little poem about taking control of your own life. I could have just taken Kris’s translation, fixed it up a bit, and called it done, but I was compelled to make the translated poem not only rhyme, but also have proper meter. Even though people watching the play would understand that it was supposed to be a poem regardless of what the subtitles were, making the extra effort allows the viewer to much more easily and naturally pick up on a truer meaning of the scene.

The Evolution of Translation

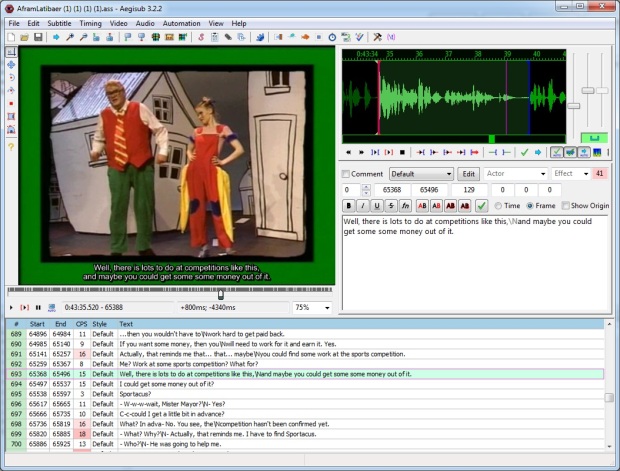

While all of the interpretation and so on was happening, I would be entering the text in to a program called Aegisub, which is subtitling software, and which I would use to properly line up the subtitles with the video. As opposed to the interpretation part of the process, this part takes no critical thinking whatsoever, but it does require meticulous precision. It’s a little more complex than just simply syncing the subtitles to the video, as there has to be additional considerations, such as making sure the lines are on screen for the appropriate amount of time, and making sure that the lines are not too long, rendering them difficult to read. The software has information that helps you know if there are any lines that might meet those criteria. This could actually get dicey at times when people were speaking very quickly, or when there were many people were talking at once, and compromises would have to be made. Sometimes, the compromise is to simply accept that a particular line is not going to be on-screen for long enough to comfortably read. Other times, the compromise would be to rephrase or reword lines to make them shorter, which is another example of how lines might get changed. The process was long, as there are 1000+ lines of subtitles in any given play, and definitely took the most time to do. After I had finally laid out all of the subtitles, and kept my brain from melting, it was time for a whole lot of reviewing.

I would review the subtitles two or three times, or however many times it took for me to feel good about them, by watching the video and keeping my eye out for both technical improvements and linguistic improvement. The technical improvements would basically be me scrutinizing the work that I described in the paragraph above, and making additional improvements to the timing and layout. The linguistic improvements include small things like grammatical errors, but would mainly be changes to the phrasing of lines to better reflect their true meaning, as the meaning can become more clear after you start to the see big picture of the conversation or scene or play, rather than seeing things line-by-line.

Working in Aegisub

After I was happy, or happy enough because I’m a bit of a perfectionist, I would then send any questions that I had or clarifications that I needed back to Kris, which he would kindly answer and the necessary changes would then be made. If for whatever reason he was not able to answer any questions, or if I still didn’t understand despite his best efforts, I would send the remaining questions to a second translator that I would hire over fiverr for a second opinion. We would go through a similar, yet much more compact, process like what has been described so far, and necessary changes would once again be made. There have been times when even after a second opinion, a certain line might still not make sense. I have never felt the need to get a third opinion on anything so far, and would just use my best guess on any lines like this.

Once the subtitles were “finalized,” it was now time for a final review where myself, Kris, and at least one other third party (it was usually Fox, who I mentioned earlier in the post) would review the subtitles. By this time, there were very little meaningful changes that could be made to the text. Most of the final changes were grammar fixes, or making minor technical changes. After everyone got their final word in, I would throw Kris a few extra dollars for his efforts because I’m just that nice of a guy, and finally, after all of that time and effort, the subtitles would be added to a video upload on YouTube for the world to see. We went through this entire process three times, once for each play: Glanni Glæpur í Latabæ, Áfram Latibær, and Jól í Latabæ, in that order.

Glanni Glæpur í Latabæ, translated

Working on these translations was quite rewarding for me in several ways. First and most obviously, it allowed me to understand the plays, which is great all by itself, however, by extension, it also allowed me to have a deeper and more clear understanding of the ideas behind LazyTown. I am now better able to understand what the characters are supposed to represent, the core values of LazyTown, the evolutionary path that it it has taken over the decades, and have been able to re-evaluate LazyTown as a whole with my new knowledge. Second, translating the plays also gave me an opportunity to understand Icelandic a little more, which is always a good thing to have up your sleeve as a LazyTown fan. Finally, and most importantly, it is very meaningful to me to have been one of the people who finally opened the door for LazyTown fans, both present and future, to have an opportunity to develop a deeper appreciation for LazyTown. To get metaphorical, I was once a sheep, and have now become a shepherd; a concept that I actively appreciate every day. I admit that every morning, you can find me checking the comments on the YouTube videos. I’m both surprised and humbled by the amount of people who are watching, and it brings me joy seeing their reactions. There are even people now using the English translation to springboard into translating the plays into other languages.

I went from having little hope that it was never going to happen, to actively making it happen in a matter of a few days, and then being done in a matter of a few months. Looking back, my hopelessness seems silly, because it really wasn’t difficult to do once we got started. The real challenge was having the patience to wait for everything to line up correctly to make the goal of translating the plays within reach. I’m very thankful for everyone who contributed to that. But enough of all of this pour-my-heart-out crap, because there is still lots to do! There is still a pretty large amount of LazyTown content waiting to be translated to English, like the group of books that were published even before the plays! I absolutely look forward to getting, and fully intend to get, all of those done and more, and to once again discover the LazyTown mysteries that are hiding just behind the language barrier.